Forget hybrid, the system is still broken.

Just last week I spoke about whether organisations are paying lip service to well-being at a national conference on Workplace Mental Health. I was also on ABC Radio with Josh Szeps discussing excess annual leave and why people don’t take holidays. Josh asked whether companies should force people to take leave, and what kind of organisational cultures and leadership behaviours contribute to people feeling like they are slacking off, or aren’t serious about their job if they use all their leave.

On Friday night a 27 year old Ernst and Young employee was found dead at the company’s Sydney office “after working until midnight following work drinks at a popular bar.” Ernst and Young have put out a statement that they will “review their work and social culture following this tragedy.”

The question begs, why after? The issues with and effects of work cultures with long work hours as a way of being have long been known. It is the peak of audit season in Australia, where employees in audit firms are often expected to work extreme hours to service clients. The psychosocial risks to employees are clear, and yet often ignored.

I’m deeply saddened to hear of the death of this employee, particularly in light of the national conference last week, and especially given the topic I was asked to speak on. Are we to believe that anything is really changing, even with the hopeful signs that a new era of work flexibility is here to stay?

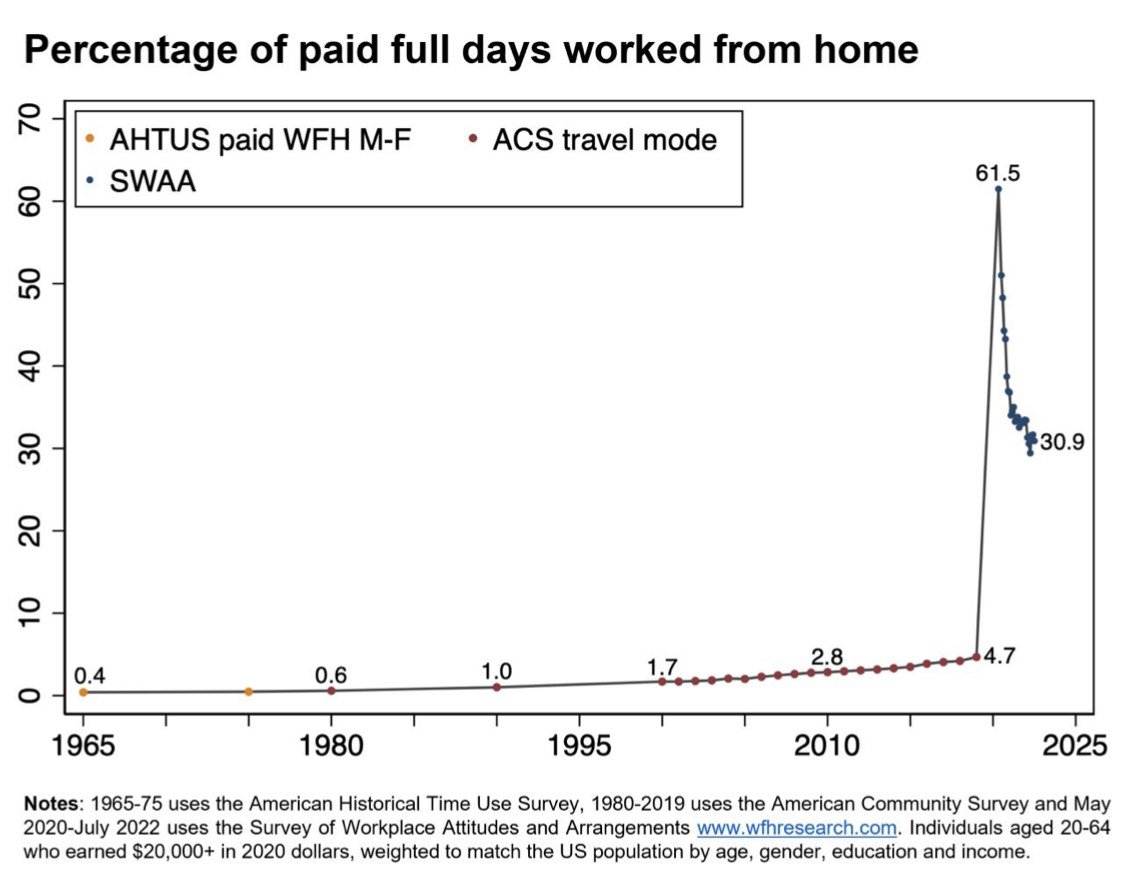

Stanford economist Nick Bloom has just released data showing that in the US work from home has stabilised at 30% of work days, a 6-fold jump pre-pandemic, saving 200 million hours and 6 billion miles of commuting a week.

This is great news. However, it isn’t enough to just change the location of where we work.

At the conference last week, I had a conversation with an Ernst and Young Director, and a senior manager from another consulting firm. The EY Director reported that she had been working 65 hours a week for at least a year.

She worked every day, night and weekend.

This Director wasn’t even in audit where the intense reporting period in audit firms is often used as a justification for the long hours. The other consultant asked her whether this expectation would go up once she became partner. The answer was yes. The EY Director commented that she was figuring out all the things she will have to stop doing or give up in the rest of her life in order to take that next step up the rung.

This conversation is chilling in light of the tragedy this week. It also indicates that indeed, WFH aside, not enough is changing. If you are expected to work 65 hours a week in order to meet your KPIs, where you do it isn’t going to make much difference to the negative effects on your physical and mental health.

If working 65 hours a week is still the entry ticket to participate high up the career ladder, then we have really made no progress at all.

Ernst and Young reported global revenues of US$40 billion dollars in the 2021 financial year. Just a few weeks ago, Ernst and Young Australia announced revenue growth of 19% to $2.75 billion for the 12 months to 30 June 2022.

Such figures perfectly exemplify the sentiment behind the rise of the anti-work movement (one of the top 5 most popular articles on BBC Worklife this year). First brought to light in a New York Times piece in August 2021, the anti-work movement’s poster child was a Chinese factory worker who quit his 9-6-6-day a week job, drew the curtains, and got into bed to ‘lie flat as a protest”. The now global trend is seen as a stand against peak capitalism, of the production of excess.

But people aren’t rejecting work outright. They are instead rejecting the dehumanisation of it. Rejecting decades of being asked to leave anything about themselves and their life that didn’t relate to work at the door when they clocked in.

What if people do want to work less? Or on multiple different things? How are organisations preparing for this? Not much, or not at all is the answer. Most are hoping that this new trend will all go away. Spoiler alert, Nick Bloom’s modelling going forward (including factoring in a recession) predicts that the new landscape of work that employees want is here to stay.

Like it or not, there is still a negative stigma in some organisations around taking large amounts of annual leave all at once. You are taking a month off? Really? I guess you aren’t that serious about your job or getting promoted.

Never mind the leadership behaviours and cultural norms at firms like Ernst and Young (who are just one of hundreds if not thousands of firms who act the same way).

I once worked in a human resources leadership role in a big law firm. Returning to the office after a public holiday, I struck up conversation with one of the most senior partners in the firm as we waited for the elevator. He told me how delighted he was after he popped into the office around 5pm on the public holiday and saw how many office lights were on, their occupants dutifully toiling away in quest of their billable hours.

I tried, probably unsuccessfully, to hide the horror on my face.

But it’s not just large organisations. Startup culture perpetuates this approach as a badge of honour. The hustle. The message is that you can’t be serious about your venture if you aren’t eating, sleeping, breathing it 24/7. In this scenario, the venture capital firm replaces the management team as the driver of the dog-eat-dog culture.

Professional services firms and large corporates of all types talk a lot about investing in their people. In their profit announcement, Ernst and Young David Larocca stated “these results have enabled us to invest an additional $150M in our people, including upwards of $70M across record bonuses, bringing forward promotions and salary rises by 3 months, additional COVID leave, parental leave and home office assistance. We also granted an additional 3 ‘EY Unplugged’ leave days throughout the year which involved proactive engagement with our clients and teams to shut the firm and give our people more time to focus on their wellbeing.”

These words have fallen tragically, and hollowly flat as emails have come to light in the media today of Ernst and Young Hong Kong bosses requiring their staff to “start work by 9.30am and finish no earlier than 11.30pm.” Bonuses, promotions, and three extra days off will not fix a broken system. We are addressing the surface problems, and rarely the root cause.

In response to the article on UPS drivers in the New York Times last week, Stanford professor and author of Dying for a Paycheck, Jeffrey Pfeffer commented “the fact that in 2022, essential workers such as delivery people (and warehouse workers, among many others) put their lives at risk because companies do not provide tolerable, safe working conditions provides evidence that rhetoric notwithstanding, the modern economy seems singularly unconcerned about people's lives.”

Pfeffer also asked a rhetorical question on the findings of a recent study he and his colleagues had completed.

“What should you do if you are a wellness director and/or CEO of a health system facing physician burnout and you see a study that U.S. physicians spend 123% more time entering orders, 53% more time using electronic health records, 160% more time processing email in-basket messages, and 33 % more time entering notes?

1) Offer doctors yoga sessions (sometimes facetiously referred to as goat yoga)?

2) Provide stress reduction workshops?

3) Offer Doordash so they don't have to cook?

4) Hold workshops on personal resilience?

5) Or, just maybe, redesign work, use AI, and redesign the hideously bad medical software that are root causes of the problem?”

We are in the early days of figuring out the new landscape of remote, hybrid and flexible work post-pandemic. No one has all the answers, or even any of them. One things seem certain however, most companies have been caught by surprise by the tsunami of desire by employees to create a way of working and living that is very different. Not just one that gives us a bit of extra time to juggle their lives while still being expected to hit benchmarks that call for 10+ hour days. Or 65 hour weeks.

It’s a little bit of back to the future honestly. Mindfulness is now mainstream in corporate America. If you tell your colleagues at a Silicon Valley barbecue that you’ve started micro-dosing with LSD, they are likely to assume you are trying to enhance your performance rather than hoping for a reincarnation of Woodstock. Companies like Salesforce are buying retreat centers for their employees.

This week is Burning Man, the infamous annual counter-culture party in the desert that celebrates artistic self-expression and building a temporarily self-sufficient community. CEOs are now regulars at the event, hoping to glean an insight into how they can create a sustainable community in the middle of the desert for only two weeks, while leaving no trace of having been there after the last cars have rolled out towards the horizon. Or perhaps they are looking for a new path out of the machine that rolls relentlessly on, existential pandemic driven human identity crisis not withstanding.

But we are tinkering at the edges. The aperture is far too narrow still. Sending employees on a breath-work retreat in a yurt is unlikely to catalyse the systemic change that is needed.

WFH is great. Mindfulness is wonderful. But none of these initiatives will address the root of many of the consequences of the design of modern work. A far bigger rethink is demanded.

The approach needs to shift from machine-centred, or system-centred. It’s not enough to be human-centred, our conversations around how we change work should be life-centred.

For confidential 24-hour support in Australia call Lifeline on 13 11 14.